The Feminist Resurrection and the Beginning of the End for the Regime

2022-09-28

On September 16, 2022, Guidance Patrol police in Tehran murdered a 22-year-old woman; allegedly, she was not wearing the hijab in accordance with Iranian state policy. In response, people across Iran have taken to the streets for almost two weeks, confronting police and opening up spaces of ungovernable freedom. For many in Iran, it appears that a revolutionary process is underway.

Collaborating with Collective 98, an anti-capitalist and anti-authoritarian group focused on struggles in Iran, we were able to interview Iranian and Kurdish feminists about the situation. Collective 98 derives its name from “Aban” 98, the uprising that spread across Iran in November 2019—year 1398 according to the Iranian calendar. In the following text, they explore the historical significance of this wave of revolt and the forces that set it in motion.

The woman whose death sparked this movement is known most widely as Mahsa Amini, thanks to news reporting and social media hashtags. In fact, her Kurdish name is Jina; this is the name by which she is known to her family, friends, and the whole of Kurdistan in Iran. Kurdish people in Iran—being an ethnic minority—often choose a Persian “second name” to conceal their Kurdish identity. In Kurdish, Jina means life, a political concept that appears in the slogan that Kurdish women have popularized in Kurdish parts of Turkey and Rojava since 2013, and which has become the central refrain of this cycle of struggles: Jin, Jian, Azadî [“women, life, freedom”].

From the revolt in Iran to the anti-war protests in Russia, from the defense of Exarchia to the student walkouts protesting anti-trans policies in the United States, resisting patriarchy is fundamental to confronting capitalism and the state. A victory in Iran would galvanize a host of similar struggles elsewhere around the world.

To keep up with developments in Iran, we recommend SarKhatism/ and Blackfishvoice on Telegram (both in Farsi) and the websites of the Slingers Collective and the Kurdistan Human Rights Network (both in English).

Jina means life: Jina Mahsa Amini.

“The beginning of the end” is the expression used in a statement issued on September 25, 2022 by “The Teachers Who Seek Justice” on the current cycle of struggles in Iran, one week after the killing of Mahsa/Jina Amini. This phrase captures the stakes of this historic moment. It implies that the proletarians on the streets, especially women and ethnic minorities, see the end of the 44 years of Islamic dictatorship as very close. They have entered into an explicitly revolutionary phase in which there is no solution but revolution.

The uprising of December 2017-January 2018 represented a watershed moment in the history of the Islamic Republic, when millions of proletarians across the country in more than 100 cities rebelled against the ruling oligarchy, saying “enough is enough” to a life governed by misery, precarity, dictatorship, Islamist autocracy, and authoritarian repression. It was the first time that society, especially the leftist students in Tehran, expressed the negation of the system as a whole: “Reformists, hardliners, the game is over!”

Over the past five years, the whole country has been on fire. You could say it is burning from both ends: between chronic nationwide riots and organized struggles involving teachers, students, nurses, pensioners, workers, and other sectors of society.1 Teachers, to give a single example, have mobilized six massive demonstrations and strikes over the past six months, each one taking place in more than 100 cities. The leaders and well-known activists of this movement have been arrested and are now in prison, but the teachers’ movement continues to mobilize.

These two levels of struggle—the spontaneous mass uprising and the more organized forms of resistance—are interrelated. Each cycle of struggle is becoming more intense and “militant” than the previous one, and the temporal gaps between the cycles are becoming increasingly shorter.

Nonetheless, Mahsa’s/Jina’s death has unleashed something qualitatively different, which must be considered a break with the historical period that started with the December 2017-January 2018 uprising.

The previous cycle of uprisings was provoked by explicitly economic intrigues (three-fold increase of fuel prices in November 2019, for example2) and directed against the widespread misery structurally engendered by authoritarian neoliberalism over the past 30 years. The economic crisis and extremely harsh class differentiation in Iran is not simply the result of the US sanctions—as the pseudo-anti-imperialist wants to make us believe—nor is it simply the result of the structural adjustments imposed by the International Monetary Fund after the Iran-Iraq war in the 1990s. While these are absolutely important factors, we see the social problems not simply in abstract and “external” terms but rather as the result of a deeper and more longstanding historical process in which the ruling oligarchy has dispossessed many populations, rendered labor precarious, commodified various domains of social reproduction, and brutally repressed syndicates, labor unions, and any other organized form of doing politics.3

We should not underestimate the catastrophic and destructive effects of the US and EU sanctions on the daily lives of people in the current conjecture, nor do we want to downplay the relevance of the past histories of “semi-colonialism” in Iran up to the present. We cannot forget the participation of the Labour Party in the UK in the 1953 coup, engineered by the Central Intelligence Agency, to overthrow the democratically elected prime minister, Mohammad Mossadegh, who championed the nationalization of the oil industry in Iran. It was precisely imperialist interventions like this that provided the social conditions for the rise of Islamists like Khomeini who hijacked the progressive revolution of 1979 and established an autocratic dictatorship.4 Rather, our position is a political negation that operates with the logic of neither/nor, criticizing the Islamic Republic and the US and its allies at the same time. This double negation is fundamental to forming genuinely international solidarities and to the cause of internationalism itself.5

Now, despite all the cycles of struggles and forms of political organizing of the past five years, this time round is different, because the riots are ignited by the killing of Jina Amini, a woman of Kurdish ethnicity, due to compulsory Hijab—the structural pillar of patriarchal domination in the Islamic Republic since the 1979 Revolution. The ethnic and gender dimension of this state killing has changed the political dynamics in Iran, giving rise to unprecedented developments.

First, the fact that protests began in Kurdistan—in Saghez, Jina’s home city, where she was born and buried—played a crucial role in what happened afterwards. Kurdistan has a peculiar position in the history of political movements and social struggles against the Islamic Republic. In the aftermath of the 1979 Revolution, when the majority of Persians in Iran said “yes” to a referendum on creating an Islamic Republic, Kurdistan said a strong “no” (see this historic photo). Khomeini declared war—more precisely, “Jahad”—on Kurdistan. What followed was an armed struggle between the Kurdish people (and Kurdish left-leaning parties) and the Revolutionary Guard (i.e., Islamist forces who took power and hijacked the revolution). Many non-Kurdish leftists also joined with Kurdistan at the time, because they saw Kurdistan as the “last bastion” to defend—the social geography in which there remained a possibility of realizing the progressive and leftists’ ideals of the Revolution. Although Kurdistan was defeated after almost a decade of armed struggle and numerous other forms of political organization, nonetheless, Kurdistan never bent the knee to the Islamic Republic.

Hence, one of the slogans that emerged after the murder of Jina was “Kurdistan, Kurdistan, the graveyard of fascists.” In the immediate aftermath of Jina’s murdering, it was Kurdish women who began chanting “Jin, Jian, Azadî” (Women, Life, Freedom), the famous slogan originally chanted by Kurdish women in Turkey and more recently in Rojava (the Northern and North-eastern parts of Syria). In Iran, this slogan has now spread beyond Kurdistan across the country to the point that the current movement, which is indeed a feminist revolution, is known by this name, “Jin, Jian, Azadî.”6

Demonstrators chanting “Kurdistan, Kurdistan, the graveyard of fascists.”

Among the three terms of the slogan, the second one, Jian [Life], has some striking features. While Jin [women] refers to gender liberation and Azadî to autonomy and self-governance, Jian, is first and foremost reminiscent of the name of the symbolic martyr of the movement, Jina Amini (as in Kurdish, Jina also means life). On Jina’s grave, her family inscribed the following sentence: “Dear Jina, you are not dead, your name become the Code.” She became the universal symbol of all previous martyrs, signifying all the other Jinas whose lives are ruined by the Islamic Republic, both directly and indirectly, because of their gender, class, sexuality, or the destruction of their ecological environment.

There is an existential component to this movement, which is also expressed on Twitter (with #Mahsa_Amini or #Jina_Amini) among the Iranian users who recount how their lives and the lives of their friends and families have been wasted over the past 44 years—tortured, imprisoned in both extra-juridical ways and show trials, their lives wasted outside of prison in everyday life without any chance to be fully actualized. Lives that did not live, as the German philosopher Theodor Adorno put it [Das Leben lebt nicht]7. Yet this melancholic recalling of the past is oriented towards the future, with an aspiration to finally put an end to the zombie Islamic Republic that drains our vital energies and life processes. There is a future to be reclaimed, a future in which no one will be killed on account of her gender or her hair, in which no one will be tortured and no one will suffer from poverty—a classless society governed by a genuine and not just formal freedom (though not everyone shares that last goal).

For what does class struggle mean, if not reclaiming life in its entirety by liberating it from the ways it has been colonized by capitalist accumulation and all the other forms of domination that sustain and secure that?

The fear of standing up to a monstrous authoritarian regime that displays no principles whatsoever has turned into its opposite: rage, power, and solidarity. The oppressed classes have never been this united since the 1979 Revolution. The videos showing sisterhood among women, united against misogynist repressive forces, have given everyone goose bumps.8 The solidarities established between the so-called “center” and the “periphery” across the country as well as among traditionally opposed ethnic minorities (between the Kurds and the Turks in the province of Western Azarbaijan) are unprecedented. The courage and determination of the youth to build barricades and fight with their bare hands or cobblestones against the police are astonishing and admirable.

Satarkhan Street in western Tehran, around 12:15 am on the first of Mehr (one of the months in Iranian calendar), September 23, 2022.

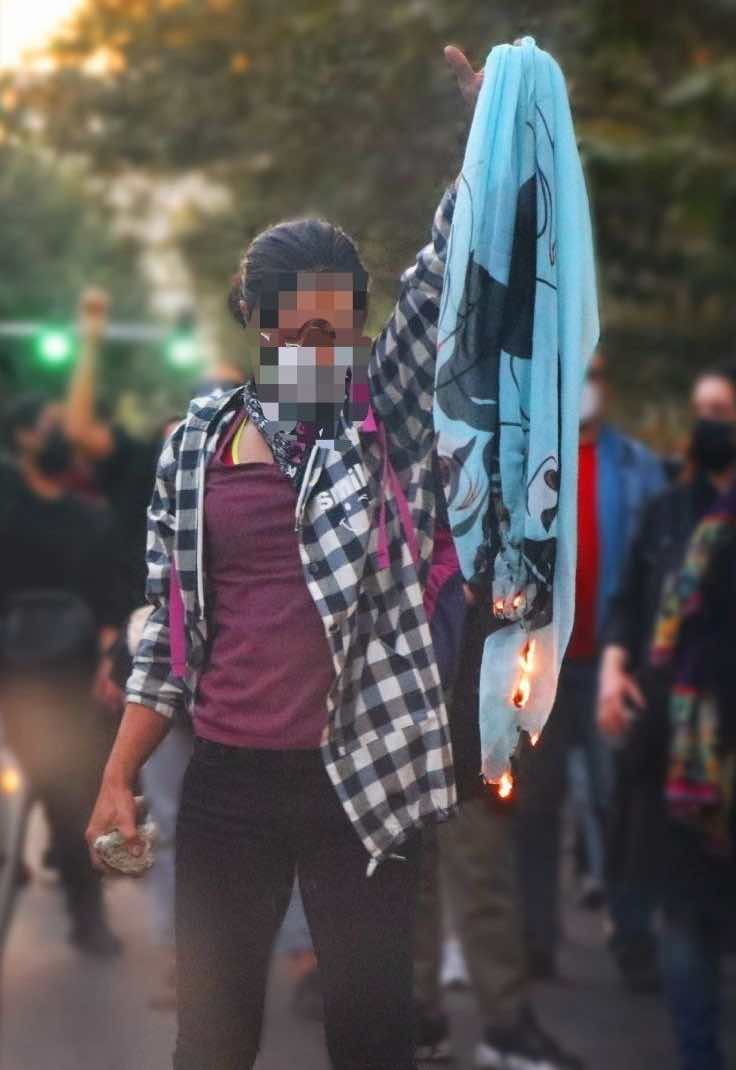

As the social class who are oppressed, dominated, and exploited above everyone else, women are at the forefront of transforming fear into rage, subordination into collective subjectivity, death into life. Women protestors courageously take off their scarves, wave them in the air, and burn them in the flaming barricades set up to hinder police violence.9 There is nothing more empowering than burning scarves in Iran: it is like burning a swastika under Hitler’s regime in the 1930s. Contrary to Western corporate media reports, the protests in Iran are not simply about the “morality police”—they represent a rejection of the structural social, political, and juridical relations that systematically reproduce capitalist patriarchy combined with Islamist codes.

As a social relation, Hijab signifies a set of constitutive elements of the Islamic Republic. First, viewed symbolically, compulsory Hijab represents the regime of patriarchy as a whole. The compulsory practice of veiling the body reminds women on a daily basis that they have an inferior position within society, that they are the second sex, that their bodies are structurally owned by the family, their brothers, fathers, male partners, and of course by the bosses and the state. Second, Hijab also represents the religious, autocratic authority that is capable—or at least, was capable—of imposing Islamic dress codes on the bodies of the ruled classes, especially women. No to Hijab means radically challenging the authority and legitimacy of the Islamic Republic as a whole. Third, and from an international standpoint, Hijab as an “Islamic virtue” is also understood by the ruling classes as the most important representative of “anti-imperialism.” Just as Adolf Hitler systematically employed the swastika to ideologically express the “prosperity” and “well-being” of a society ruled by National Socialism, the Islamic Republic has imposed Hijab on women to convey the impression that Iranian society is constituted by the realization of Islamic virtues and ideals and therefore fundamentally opposed to the Western empire and its moral values and social norms. Hijab thus allegedly represents an ideological and practical alternative to the empire.

In the immediate aftermath of the Revolution, on March 8, 1979, tens of thousands of women marched in the streets of Tehran against the imposition of compulsory Hijab, chanting “Either a headscarf or a head injury” and “We did not make a revolution to go back”—referring to the reactionary aspect of compulsory Hijab that aims to “turn back” the wheels of history. At the time, the Islamist media and Khomeini labeled the feminists and other women on the streets as supporters of imperialism who subscribed to “Western culture.” Tragically, no one heard the women’s voices or heeded their warnings, not even the leftists who—catastrophically—accorded an ontological priority to the struggle against imperialism, relativizing and downplaying all other forms of domination as “secondary.” Today, when women burn scarves on the streets and the whole society emphatically rejects compulsory Hijab, this shakes the entire patriarchal and autocratic authority to the core, along with the pseudo-anti-imperialist legitimacy of the Islamic Republic. These are the pillars of class rule in Iran and the whole population is rejecting them. The Islamic republic is already dead in the minds of its people; now the people must kill it in reality.

Let’s be clear: burning scarfs is not a right-wing gesture oriented towards a fascist Islamophobia. No one is challenging anyone’s religion. Rather, it is a gesture proclaiming emancipation from compulsory Hijab, which controls women’s bodies. Hijab has nothing to do with “women’s culture” in the Middle East, as some postcolonial thinkers imply. In the context of the Islamic Republic, Hijab is a method of class domination, an integral part of capitalist patriarchy, and must be criticized without compromise.

As a historically specific social relationship, capitalism has the capacity to employ “non-capitalist” social relations at the service of its own accumulation and reproduction. Religion, like patriarchy, is not a thing of the past; it is not an anachronistic residue that lies beneath the surface of modern society without social effectivity. In a capitalist society like Iran, class domination as a whole is mediated by and recoded via Islamic codes. Compulsory Hijab has been a crucial element in the Islamic Republic patriarchy that has marginalized women and systematically controlled their bodies. This has also led to a division within the working class in the broad sense of the term through gendered hierarchies and interpersonal domination.

The pseudo-anti-imperialists who think that the people on the street are simply the puppets of Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the United States not only deprive the people of their agency and subjectivity in a typically orientalist manner by presupposing an “abstract essence” for a society like Iran—they also reproduce the reactionary discourse and practice of the Islamic Republic itself. Understanding this is crucial for international solidarity with women in Iran and the oppressed classes more generally. Strikingly, even the religious Muslim women who wear Islamic dresses like the chador have emphatically rejected compulsory Hijab and supported this movement on the streets and social media.

With women at the forefront of the struggles fighting courageously against the repressive apparatus of the state, the Islamic Republic has never appeared so weak. The question is not “what is to be done,” but how to finish it off?

Kurdistan initiated the protests and introduced feminist and anti-authoritarian slogans. This catalyzed the students—the social sector that is always at the forefront of political events—in universities, especially in Tehran, to organize protests and expand the uprising via their assemblies and sit-down strikes. Like COVID-19, in the timespan of the two days following Jina’s death, the uprising spread across the whole country; so far, the oppressed classes have fought with tooth and nail against the regime’s repressive forces in more than 80 cities across the country.

Because we have entered an explicitly revolutionary stage, the street conflicts between the protestors on the one hand and the police and Basij (the militia organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps) on the other have become less “one-sided” than before. People have realized that, with social cooperation, solidarity, and practice, they too can exhaust the repressive forces and finally shut them down. Young people especially are learning various methods of self-defense, such as making a “handmade nail screw” that punctures the tire of police motorcycles and prevents them from moving freely to carry out attacks. Independent doctors are announcing their mobile numbers on the internet to help those who are injured in the protests, as going to the hospital is often dangerous. There are also calls for “neighborhood organization,” a local structure to connect those who live in the same area.

Given that the ideological apparatus of the government has become dysfunctional for most of the society, the chief medium through which the Islamic Republic continues to reproduce itself is the repressive apparatus that, during this uprising alone, has already killed 80 people and arrested thousands of protesters.10 Let us not forget that this occurred during an internet blackout, a brutal method that the Islamic Republic has repeatedly employed in the past, especially during the 2019 November uprising—Abaan-e-Khoonin [“Bloody November”]—when “the authorities completely shut down the internet for four successive days, transforming the country into a big black box, slaughtering the people with impunity.”11 Jina Amini also represents and calls to memory the hundreds of martyrs who were murdered at that time.12 Those who support the Islamic Republic on the grounds that it is an anti-imperialist force in global geopolitics conveniently ignore that it murders its own people on the streets, imprisons them illegally, and tortures them to extract false confessions.

Now, after ten days, the prospects of this cycle of spontaneous mass uprising depend on the more organized forms of resistance, especially the strike of workers, teachers, and students. In Iran, unlike the most advanced capitalist societies, unions and syndicates are not integrated into the capitalist system. Unions do not simply aim to realize their own particular demands, thus hindering the formation of a more radical movement. Rather, they seek fundamental transformations that the ruling classes see as an existential threat. This is the reason why hundreds of union members and syndicates (teachers, students, workers, pensioner activists) are currently in prison, some of them tortured.

Over the past four days, there have been many calls for a “general strike” from progressive students and teachers and also some anonymous militants who produced agitational videos using revolutionary songs produced in the aftermath of the 1979 Revolution. Oil workers have also threatened to go on strike if the Islamic Republic continues to repress the protests on the streets.13 If this happens, then the whole dynamic will change.

What is certain is that the uprising needs new energy, an event that enables it to keep going, as it is very difficult to sustain such an uprising on a daily basis over a long period of time. More generally, beyond the immediate exigencies of the present, overthrowing the Islamic Republic hinges very much on crucial organizational questions that require not only a “collective intellect” but also time to put it into practice via trial and error. The missing link is an organic relationship between the spontaneous mass uprising and other organized forms of struggle. This implies that each side of this relation becomes more organized internally, through the formation of local-countrywide organizations and more coordinated actions among the unions and syndicates.

Most importantly—and this is crucial for international solidarity—the radical trends within the movement need to be promoted, while the reactionary elements should be criticized. The revolution that society seeks is not simply a political one in which the autocratic Islamic Republic is displaced by another—say, a more democratic-liberal—political form. It is also a social revolution in which not only the individual subjectivities of the people but also the most important social structures are transformed. Corporate media in the West (for example, the BBC Persian and Iran International) as well as celebrity activists like Masih Alinejad (who work with the most conservative forces in the United States, those in favor of prohibiting abortion and “regime change” via military intervention) are doing their best to promote the reactionary trends within the movement, reducing the whole problem to the question of “human rights.” They mispresent the social relations that emerge from the structures of capitalist societies as merely juridical ones. Their manipulative propaganda portrays a reactionary alternative, injecting doses of “loyalism” into the popular imagination: a politics that aims to revive the social-political order overthrown by the 1979 Revolution.

The people on the streets are not stupid; they do not put much stock in this narrative. It is important for our internationalist comrades across the world to support the radical trends and slogans of the movement, opposing the loyalist diaspora who are spreading nationalism by bringing the flag of Persia before the revolution of 1979 to demonstrations.

The problem is not just how to overthrow the Islamic Republic, but how to defend the revolution and its progressive forces after its toppling. The more support radical forces and progressive elements receive, the easier it will be to defend the revolution against reactionary forces. The Islamic Republic plays a crucial role in the global accumulation of capital (via the supply of raw materials such as oil and gas) and also in geopolitical power relations in the Middle East. Clearly, regional and global powers will do everything they can to shape the revolutionary process and its outcome to align with their own economic and geopolitical interests. Only with strong international solidarities supporting the most radical tendencies within the movement could the yet-to-be revolution maintain itself against the reactionary forces of loyalism, against geopolitical interventions, and against the violent integration into global circuits of accumulation.

The future is marked by uncertainties. Yet, class struggle from below and against all forms of domination will remain an important material force in the course of capitalism’s history. Of that much, we are certain.

Appendix: Kurdish Left Feminists on the Feminist Uprising in Iran

A statement written and signed by leftist feminists from Kurdistan on the current feminist insurrection in Iran.

You are hearing our voice from Kurdistan. This is a collective voice of leftists and marginalized feminists from a geography whose history is marked by discrimination, imprisonment, torture, execution, and exile. This has been the case since the early days of the 1979 Revolution. We are Kurdish women and queer people who inherited a history that is not only full of violence but also of struggle and resistance. We have always had to fight on multiple fronts: in one battleground, against the patriarchy of Kurdish and non-Kurdish men, and in the other one, against the regime’s Islamist fundamentalism and the imposition of its gendered hierarchy. Against the chauvinist feminists, we have been fighting very hard to articulate gender oppression in its intersectionality with various forms of domination imposed upon us as ethnic-national minority.

Today, we are all witnessing a feminist revolution in Iran in terms of form and content. The Kurdish slogan of “Jin—Jiyan—Azadî” (“Women—Life—Freedom”) has become the central refrain of this cycle of struggles, giving it a new and fresh life. We express our uncompromising support for the struggles of the people in Iran, especially for the women’s courageous and unstoppable fights on the streets. Since the current uprising is born out of Jina Amini’s killing by state femicide, we would like to name this uprising after Jina: “the movement of Jina” [“the movement for life”]. The name Jina in Kurdish means both life and life-giving, reminding us of Jiyan, the middle term of the slogan now chanted everywhere. For us, Jina is an appropriate name because we believe “Berxwedan jiyan e” [a reference to the Kurdish slogan, “life is resistance”].

This uprising has not only elevated the question of gendered and sexual oppression to a public concern but also shown in practice how gendered, ethnic, and class forms of oppression can be articulated in a radical manner, namely as mutually interrelated. This political articulation has enabled the protestors to form a strong and united front against dictatorship, political Islam, chauvinism, patriarchy, and the domination of capital. Those women and queer people who have brought social struggles from the so-called “private” sphere to the “public” sphere, from the domestic domain to the streets, are genuinely inspiring to us, for they have shown that the liberation from patriarchy, the state, and capital are deeply intertwined.

Let us not forget that we are at a critical conjuncture, a crucial turning point in history. Jina has become our common code, uniting us in these multi-faceted and difficult circumstances. We see ourselves as part of the social movements that seek justice for the killing of all Jinas, especially the feminist and leftist movement that opposes femicide and queer killing, whilst also taking a stand against “exclusive nationalisms” (be it on the side of the left or the right).

“Jin—Jiyan—Azadî” originally appeared in the struggles of Kurdish women in Turkey and recently became one of the main slogans in Rojava; in Iran, it spread in the blink of an eye to every corner of the whole country. What is inspiring about the slogan is that it can overcome the borders historically established by colonial and imperialist forces in the Middle East—just as the Kurdish, a nation without the state, have done in the region, especially Kurdish women. We take this transnational and transborder unity as indicative of the strength of the Kurdish women’s movement, indeed as a bright omen. Just as we see ourselves as an integral part of the women’s protests and queer communities in Iran, so too, we utilize the buildup of women’s and queer people’s historical experiences in other parts of Kurdistan in Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. “Jin—Jiyan—Azadî,” traditionally used in the funeral of Kurdish martyrs, is now chanted in the funeral of our martyr, Jina Amini. This enables us to speak of women’s power, subjectivity, and courage in their fight against the patriarchal forces driven by death and enslavement.

Sparked by the state femicide of Jina, the current uprising quickly turned into a movement against mandatory Hijab in particular and in favor of overthrowing of the regime more generally. The movement has been able to challenge, indeed to deconstruct, the prevailing narratives and images depicting Kurdish women as well as the women of other ethnicities in Iran, in two specific respects. First, the nationalist’s racist misrepresentation of ethnic minority women as simply puppets in the hands of political parties with no agency of their own. Second, the Western orientalist view of Middle East women.

The regime’s repressions and atrocities are not news to anyone. Since its violent establishment in the aftermath of the 1979 Revolution, the Islamic republic’s response to all social conflicts has always been repression—namely, the imprisonment and the killing of protesters. Like many other people in Iran, hundreds of women and feminist activists have been arrested during the past two weeks and are in prison now. Women and queer people, however, have shown that fear can no longer prevent them from participating in the various movements growing in society. They can and already have become the pioneers of overthrowing masculine dictators and oligarchs in the region as a whole.

What is happening now in Iran promises the beginning of a new historical era of fighting against violence, fundamentalism, and deprivation of the right to life. We consider ourselves part of this movement, inviting the leftist and feminist/queer groups throughout the region and the Global South to join us in this war. We are calling for Kurdish, Turkish, Arab, and Baloch feminists to join us in order to redefine the intersectionality of the various forms of domination imposed upon all of us in a progressive manner, namely: beyond the patriarchal formulations of ethnic oppression. We also call for the anti-capitalist and anti-racist feminists in the “West” and other part of the world to support our cause and stand beside us. The ideals of freedom and emancipation cannot be realized without reclaiming the right to our lives; this is what precisely echoes in Jin—Jiyan—Azadî. Our feminist revolution is following this slogan very carefully, thereby demanding a genuinely global solidarity for its realization in practice.

Further Reading

- The Beating Heart of the Labor Movement in Iran—On neoliberalism and resistance in Iran

- The Bread of Freedom, the Teaching of Liberation—An interview with a teacher about the teachers’ movement by Collective 98 (Farsi)

- Iranian Pseudo-Anti-Imperialism

- There Is an Infinite Amount of Hope, but Not for Us

For background on the 2019 November uprising, see the Collective 98 statement in Roar Magazine, signed by more than 100 hundred militants, activists, and academics. For an analysis of neoliberalism in Iran, read this. ↩

For more information on the 2019 November uprising, see the text Collective 98 wrote on its first anniversary. ↩

For more on the question of pseudo-anti-imperialism, read this. ↩

John Newsinger, The Blood Never Dried: A People’s History of the British Empire (London: Bookmarks Publication, 2006), ‘Iranian Oil’, pp. 174-77. Asef Bayat, Revolution Without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of Arab Spring (Standford, California: Stanford University Press, 2017), pp. 2-7. ↩

See the open letter from Collective 98 to ACTA, one of the most important leftist platforms in France, which published a catastrophically ideological piece from the standpoint of pseudo-anti-imeprialism on the praise of Ghassem Suleimani, the military general of the Revolutionary Guard—who not only repressed dissidents in Iran but also destabilized Iraq, Syria, and indeed the whole region. ↩

For more perspective on this slogan, consult the interview RadioZamaneh conducted with the leftist activists inside Iran who called for a general strike. ↩

Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life ↩

See the famous photo taken in Tehran, a few minutes after midnight, in which three women, joining hands, wave their scars in the air behind burning barricades. ↩

See, for example, this viral video in which women burn their scarves and dance around a fire. For some Iranian feminists, this was reminiscent of the witches before the rise of capitalism. ↩

For statistics detailing the killings and arrests in Kurdistan, consult this report. ↩

As discussed in the statement that appeared via ROAR Magazine. ↩

304 to 1500 The real number of victims is not clear. Amnesty International confirms that at least 304 people were killed, while Reuters reports 1500 people. ↩

For an analysis of the recent strike by oil workers, see Iman Ganji and Jose Rosales, “The Bitter Experience of Workers in Iran—A Letter from Comrades.” ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment